The Immune System Stimulates Inflammation in the Pore Right From the Start

The Essential Info

Even though acne is such a common disease, we still don’t know precisely how it forms. This makes treating acne a challenge, but also makes studying acne endlessly interesting as new discoveries come to light.

One such recent discovery is the central role that inflammation plays in acne development. From what scientists are uncovering, inflammation is involved in every phase of acne development, right from the start.

This article will go in-depth into how acne forms, with an emphasis on inflammation. If you want to read a more straightforward and simple article outlining what is acne, click here.

In Brief: Traditionally, researchers believed that acne was caused by male hormones that are present in both males and females. The view was that increased male hormones led to more skin oil production and clogged pores. Inside these clogged pores, skin oil would build up, and acne bacteria would thrive on the trapped skin oil, ultimately causing inflammation in the skin and acne lesions. Recent research, however, has found that inflammation is present right from the start. Because of this new knowledge, researchers now classify acne as a chronic inflammatory disease, and not just a hormonal and bacterial affliction.

Feeling geeky yet? If so, read through the entire article and then bore your friends with all the details

The Science

In the past, scientists thought that inflammation was one of the last steps in acne development, and they thought it went something like this:

- First, androgen (male hormone) level increase.

- This causes skin oil (sebum) to be overproduced and skin cells (keratinocytes) to also be overproduced.

- This leads to clogged pores.

- Inside clogged pores sebum gets trapped. Acne bacteria (C. acnes), which lives on skin oil, overgrows in the trapped sebum, and this causes inflammation in the skin and what we know as acne lesions.

You can see that inflammation is the end of the story, not the beginning. However, new research has come to light in the past few years that shows us that inflammation is actually present right from the start. So, basically, throw out what you just heard. It’s a bit backwards, and it’s now thought that inflammation is there right from the very beginning.

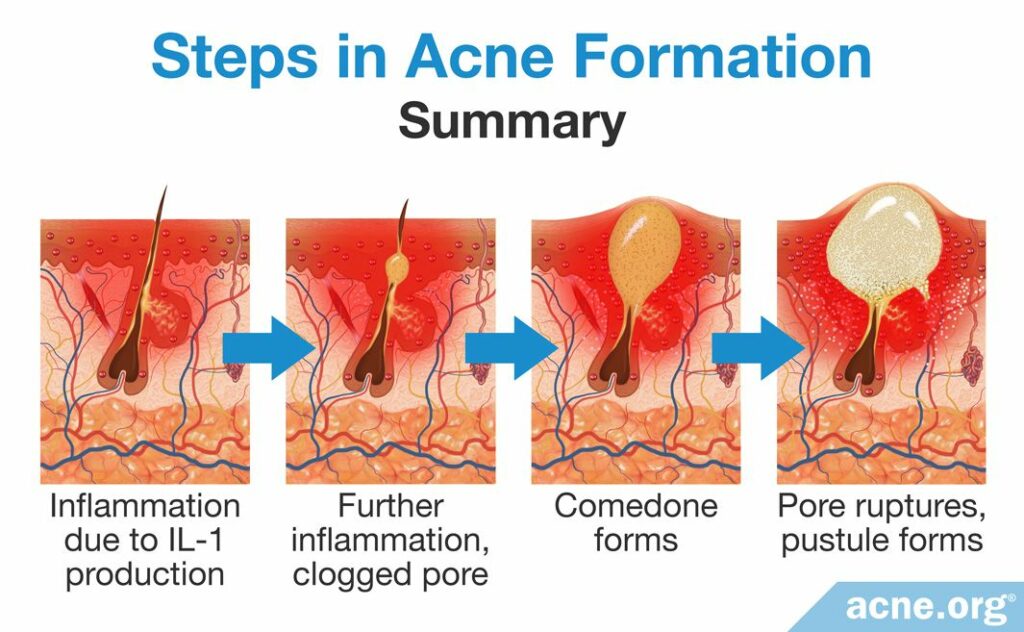

Now that we know inflammation is there from the start, here are four steps to acne formation based on our newfound knowledge. As you read, the science is going to get pretty deep, so I suggest you study each step’s picture first so you can follow along better.

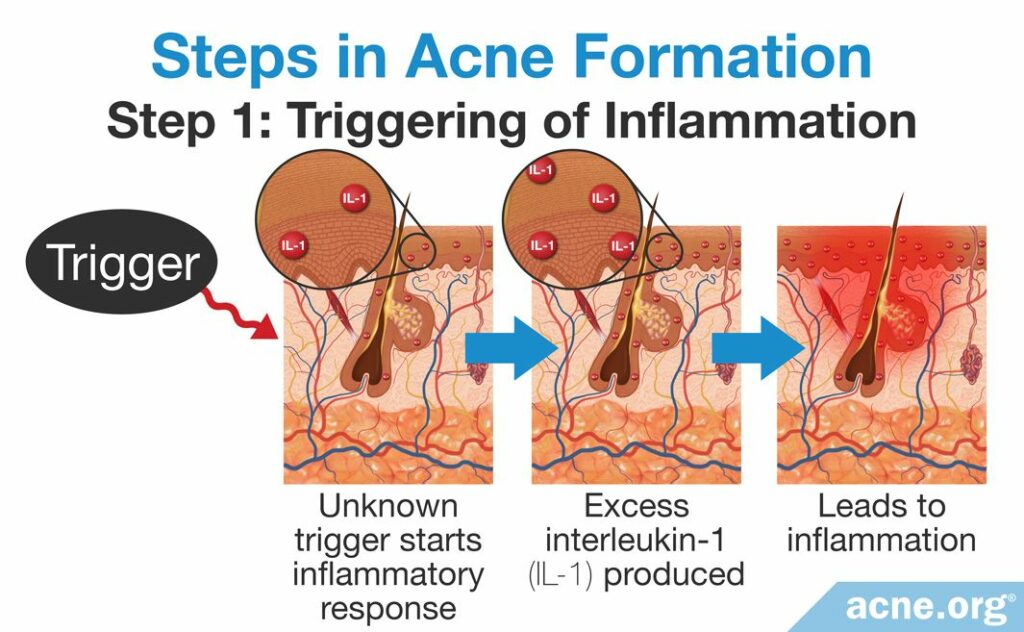

Step 1: Triggering of Inflammation

Although scientists see inflammation in the skin right from the start, they still don’t know exactly what triggers it. But they have put forth a hypothesis that might explain it.

The hypothesis: The main type of skin cell in our skin (called keratinocytes) constantly produce inflammatory molecules at low levels that act as a “surveillance system” to detect bacteria or something else that requires an immediate immune response. When triggered by something, this surveillance system will then increase its production of inflammatory molecules and cause inflammation. This inflammation can then induce changes in the tiny hair follicles that cover our skin (often called pores), leading to acne.

In support of this hypothesis, researchers have found that skin cells in all people do in fact regularly release an inflammatory molecule called interleukin-1 (IL-1) at low levels.1-4,5

So what factor(s) might trigger inflammation? Suspects include:

- Acne bacteria (C. acnes)

- Changes in skin oil (sebum) composition

- Stress

But other factors, or a combination of factors, may be at play.

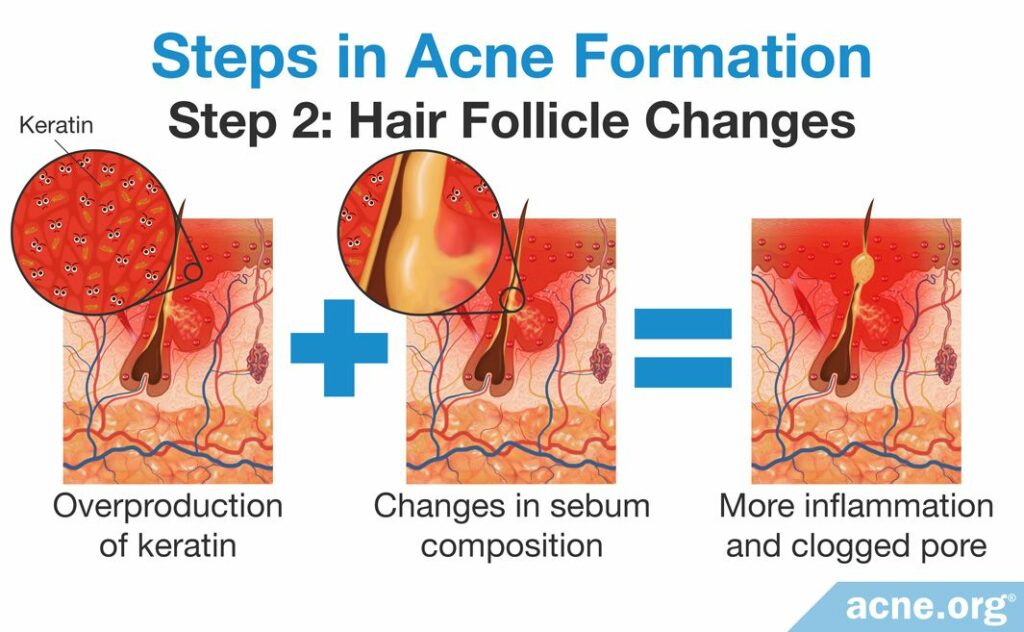

Step 2: Hair Follicle (Pore) Changes

Once inflammation is present in a hair follicle, it begins to stimulate an overproduction of the sticky skin protein, keratin. Changes in sebum composition also become evident at this point.

The overproduction of keratin and different composition of sebum may then stimulate even more inflammatory molecules, such as IL-1, and the formation of a clogged pore (comedone).4-6

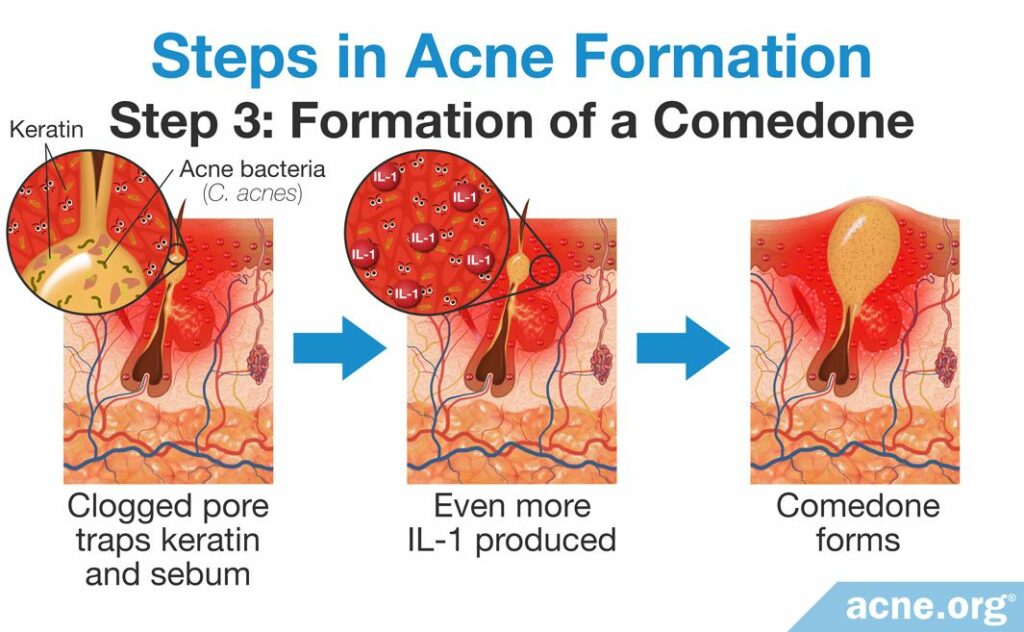

Step 3: Formation of a Clogged Pore (Comedone)

The clogged pore traps sebum and excess keratin, which begins to build up. This provides the perfect breeding ground for C. acnes bacteria.

C. acnes can lead to increased production of the inflammatory molecule, IL-1. The increase in IL-1 then leads to additional stimulation of keratin production. This further clogs the pore, and as sebum and keratin continues to build up inside the pore, a comedone (whitehead or blackhead) is formed.7-10

Note: C. acnes is found in most, but not all, acne lesions, so it can’t be the only factor that leads to the increased production of IL-1.

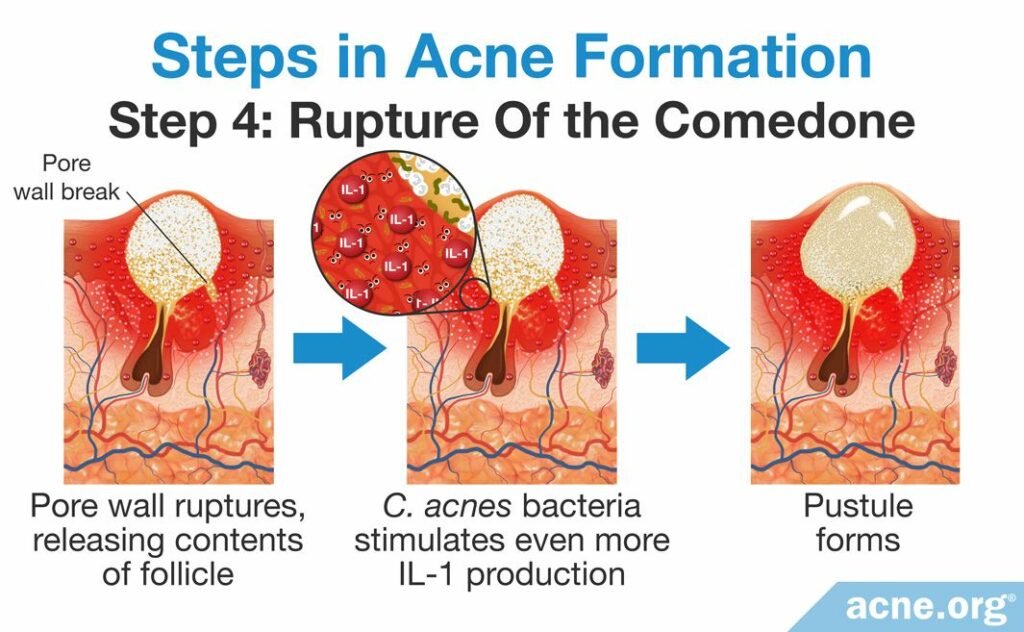

Step 4: Rupture of the Clogged Pore (Comedone)

Eventually, the buildup of keratin, sebum, and, usually, C. acnes, puts pressure on the pore wall. The pressure becomes too high and causes the wall to rupture, releasing the pore’s contents into the surrounding skin.

The body’s immune system reacts to the contents of the pore as a “foreign invader” and reacts with much more inflammation, which leads to the production of red and sore inflammatory acne lesions, such as a pustule.

Note: Even though C. acnes is not found in all acne lesions, it is found in most of them. Scientists have found that C. acnes often contributes to the rupture by producing proteins and recruiting cells that facilitate pore wall damage. After release into the surrounding skin, C. acnes can cause additional inflammation by interacting with certain immune system cells and stimulating more production of IL-1.11,12 In other words, when C. acnes is around, it most likely contributes to the pore wall break, and after the pore wall break, also most likely contributes to the production of more inflammation.

Conclusion – Inflammation Is There All Along

Beginning with an unknown trigger, the immune system stimulates inflammation in the pore.

This initial inflammation then triggers changes in the pore that include overproduction of keratin and changes in sebum composition, which clogs the pore.

These factors, usually combined with C. acnes growth, result in even more inflammation and the formation of a clogged pore.

Eventually, the pore becomes overfilled with keratin, sebum, and, usually, C. acnes, which results in the rupture of the pore.

The rupture stimulates further inflammation as the follicular contents come into contact with surrounding skin, causing red and sore inflamed acne lesions.

Therefore, the main challenge in treating acne is to reduce inflammation. This is difficult since we do not know exactly what triggers the inflammation in the first place. However, some experts speculate that inflammation may be kept at bay by a three-pronged approach:

- Restoring the health of the outer layer of skin: The outer layer of skin, also known as the skin barrier, should be kept healthy. That means avoiding excessive physical irritation, and keeping the skin hydrated.

- Keeping C. acnes in check: Normally, various bacteria living on the skin exist in a balance, preventing the overgrowth of any one type of bacteria. Using topical products like benzoyl peroxide that can reduce the growth of C. acnes may help restore this balance.

- Regulating the amount and composition of sebum: Since overproduction of sebum is a key step in the development of acne, therapies that aim to reduce sebum may help. As changes in sebum composition also appear to contribute to acne, future treatments may focus on re-establishing healthy sebum composition.13

References

- Danby, F. W. Ductal hypoxia in acne: Is it the missing link between comedogenesis and inflammation? J Am Acad Dermatol 70, 948 – 949 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24742839

- Cunliffe, W. J., Holland, D. B. & Jeremy, A. Comedone formation: Etiology, clinical presentation, and treatment. Clin Dermatol 22, 367 – 374 (2004). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15556720

- Kircik, L. H. Advances in the understanding of the pathogenesis of inflammatory acne. J Drugs Dermatol 15, s7 – s10 (2016). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26741394

- Williams, H. C., Dellavalle, R. P. & Garner, S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet 379, 361 – 372 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21880356

- Tanghetti, E. A. The role of inflammation in the pathology of acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 6, 27 – 35 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3780801/

- Zouboulis, C. C., Jourdan, E. & Picardo, M. Acne is an inflammatory disease and alterations of sebum composition initiate acne lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 28, 527 – 532 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24134468

- Kistowska, M. et al. IL-1β drives inflammatory responses to Propionibacterium acnes in vitro and in vivo. J Investig Dermatol 134, 677 – 685 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24157462

- Li, Z. J. et al. Propionibacterium acnes activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in human sebocytes. J Investig Dermatol 134, 2747 – 2756 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24820890

- Thiboutot, D. M. Inflammasome activation by Propionibacterium acnes: the story of IL-1 in acne continues to unfold. J Investig Dermatol 134, 595 – 597 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24518111

- Selway, J. L. et al. Toll-Like receptor 2 activation and comedogenesis: implications for the pathogenesis of acne. BMC Dermatol 13, 1 – 7 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24011352

- Toyoda, M. & Morohashi, M. Pathogenesis of acne. Med Electron Microsc 34, 29 – 40 (2001). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11479771

- Contassot, E. & French, L. E. New insights into acne pathogenesis , Propionibacterium acnes activates the inflammasome. J Investig Dermatol 134, 310 – 313 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24424454

- Dréno, B. What is new in the pathophysiology of acne, an overview. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 31, 8-12 (2017). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28805938/

The post Exactly How Does Acne Form Now That Scientists Believe It Is Primarily Inflammatory? appeared first on Acne.org.